Rust Advanced Lesson

overview

Rust[1] is a compiled semantically enhanced modern programming language with syntax loosely similar to C++[2] that provides the built-in cargo[3] package manager, modules[4] and the rustup[5] tool chain installer.

Rust is suited for embedded processing, fault-tolerant mission critical systems, concurrent processing with channels[6] for transferring values between threads, and it provides package abstraction and import, various pointer[7][8] implementations, including references[9], raw pointer[10], owned pointer and the borrowed[11] pointer, reborrowing [12], and lifetime[13], generic types, powerful traits[14], allocators[15], including no-heap allocation, closures[16], mutable[17][18] and fearless concurrency[19] paradigm, and closures[20]. Like C++ it has destructors[21] via Drop[22] scope as well as control over allocation and will be imminently suitable for resource management. Rust also supports operator[23] overloading[24] via traits.

Rust provides async/await keywords that provide async[25] programming through the Future[26] trait, with the .await method, provides concurrency synchronisation via futures::join!, futures::select! macros and spawning[27] provided to support mixing OS threads and async Tasks. The executors for async operations are not embedded in the language, instead are provided by runtime[28] libraries. Async programming maps well to streams[29] and web-development[30].

Rust also provides the unit type and the usual array and the additional compound types tuples[31].

Rust provides rustup[5] for tool-chain management and supports cross-compilation[32] for many platforms - thus providing good portability. I can see it being very useful in the world of prolific IoT devices, as well as in large complex systems.

Rust has several call-by mechanisms and entrenched with this is object lifetimes[33] management and access that is enforced by the compiler:

// Examples of methods implemented on struct `Example`.

struct Example;

type Alias = Example;

trait Trait { type Output; }

impl Trait for Example { type Output = Example; }

impl Example {

fn by_value(self: Self) {}

fn by_ref(self: &Self) {}

fn by_ref_mut(self: &mut Self) {}

fn by_box(self: Box<Self>) {}

fn by_rc(self: Rc<Self>) {}

fn by_arc(self: Arc<Self>) {}

fn by_pin(self: Pin<&Self>) {}

fn explicit_type(self: Arc<Example>) {}

fn with_lifetime<'a>(self: &'a Self) {}

fn nested<'a>(self: &mut &'a Arc<Rc<Box<Alias>>>) {}

fn via_projection(self: <Example as Trait>::Output) {}

}

- pass by reference is a "move" of the pointer

- pass by mutable reference permits the function to modify the referenced object

- pass by box means the the Boxed item will be deallocated when the function goes out of scope. A Box implements Drop and owns its pointer

- Rc is a smart pointer that implements a reference count; the reference count is increased on each call to a function or when cloned, until the object is no longer referenced by code.

- Arc[34] is an atomically referenced counted object and may be used in multithreaded context.

So I am going to trial switching critical system development over to this new language platform. I can't wait to put it to use and I already have bunches of ideas in the backlog.

Rust uses copy/destroy move[35] when passing parameters; the old variable reference is no longer valid after such a move, and access constraint will be enforced by the compiler to prevent accessing the original value that was moved. Here is a brief explanation of the call by semantics:

- the Rust provision is described in the rustbook[36]

- cargo is described in the cargo[37] book

- the rust language is described in the rust language book[38]

- the rustc compiler is described in its own reference[39]

The standard library is described in the std[40] cargo reference.

I expect that rust will displace C++ as the language of choice for safe embedded and complex system development despite the steeper learning curve. Of interest is it can be used for web-application development.

rust ideas

- rust on raspberry pi

- rust CID

- rust cargo proxy

- rust async IO for raspberry pi

- rust cargo repository mirror

reference code

Example code[41] is provided https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/

Plus there are other interesting aspects:

- HAL

- RPAL raspberry pi HAL https://github.com/golemparts/rppal

example codes

- getting started https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch01-00-getting-started.html

- text to morse code https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/embedded-rust-programming-on-raspberry-pi-zero-w/

- mqtt https://betterprogramming.pub/rust-for-iot-is-it-time-67b14ab34b8

platforms

- pico https://allianceforthefuture-com.ngontinh24.com/article/getting-started-with-rust-on-a-raspberry-pi-pico-part-1

- ESP32 https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-idf/en/latest/esp32c3/hw-reference/esp32c3/user-guide-devkitm-1.html

This is a teach yourself category:Advanced Lesson - see the #training for video lessons.

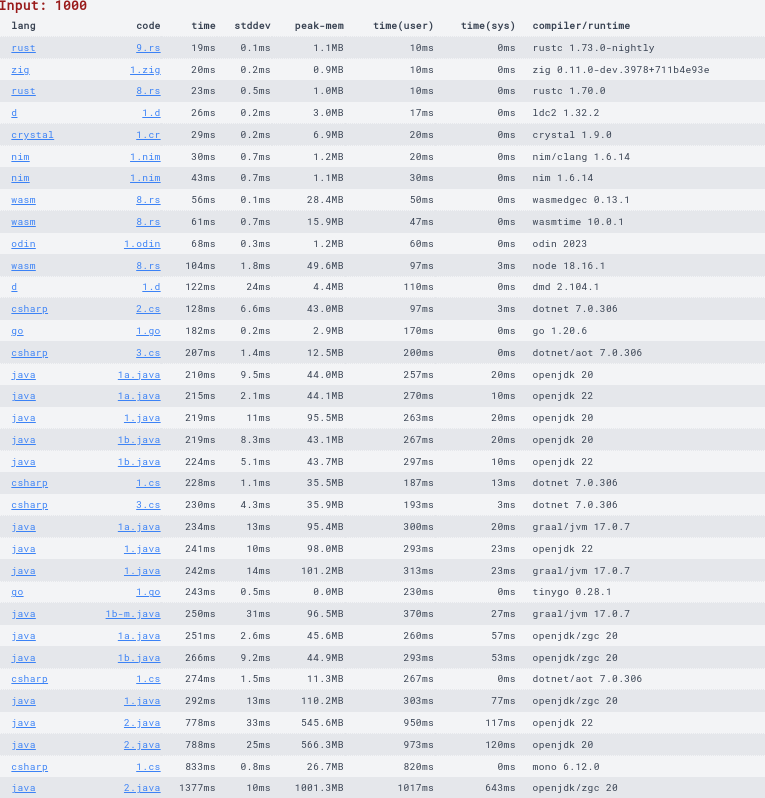

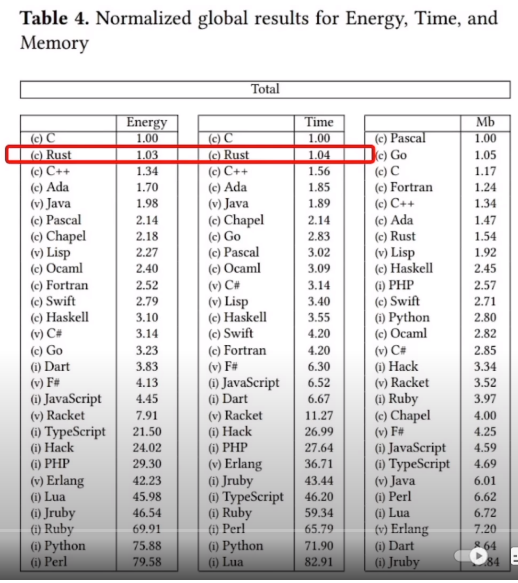

performance

Rust is a statically evaluated language that has no garbage collection, and the compiler asserts preconditions with the goal to providing safe concurrent programming. It uses the LLVM toolchain and its resultant executable code performs quite well.

native applications

These graphs are from comparative benchmarks of the simple algorithms that are easily written in other languages.

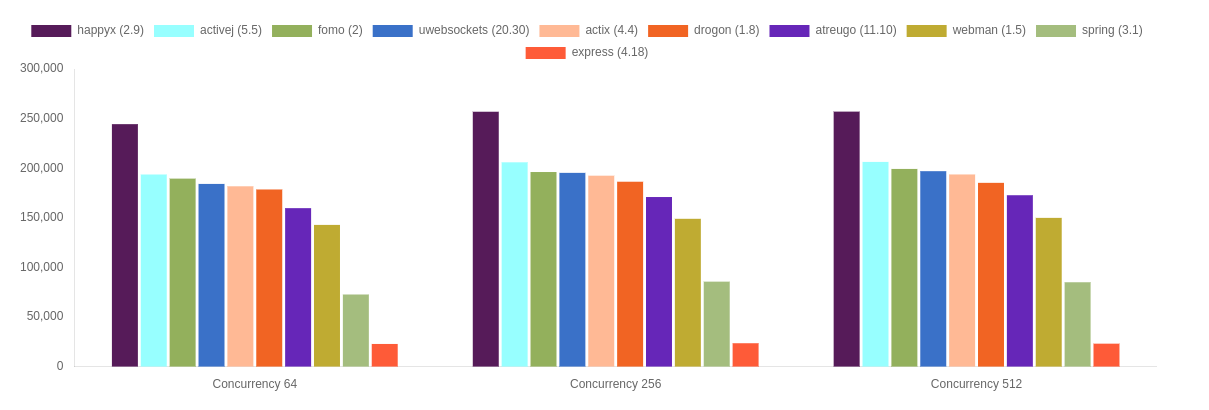

web application-frameworks

These web-benchmarks compare different application frameworks written in a candidate language:

The frameworks and their implementation languages:

- happyx - nim https://github.com/HapticX/happyx

- activej - java https://activej.io/

- fomo - php https://github.com/fomo-framework/fomo

- uwebsockets - C /C++ https://github.com/uNetworking/uWebSockets.js

- actix - rust https://actix.rs/

- drogon - C++ https://github.com/drogonframework/drogon

- spring - java https://spring.io/

- express - node-js

installation

Rust is installed via the rustup installer[45]

- on Linux download rustup and execute as regular user:

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

- or on windows use the installer

https://static.rust-lang.org/rustup/dist/i686-pc-windows-gnu/rustup-init.exe

If you have installed rust before then you may update it to the latest via rustup

- update

rustup update

- verify

cargo --version cargo 1.71.0 (cfd3bbd8f 2023-06-08)

- uninstall via

rustup self uninstall

cargo

Cargo[46] is the package manager that may be used to build, document and also run rust applications.

The project layout:

.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── src/

│ ├── lib.rs

│ ├── main.rs

│ └── bin/

│ ├── named-executable.rs

│ ├── another-executable.rs

│ └── multi-file-executable/

│ ├── main.rs

│ └── some_module.rs

├── benches/

│ ├── large-input.rs

│ └── multi-file-bench/

│ ├── main.rs

│ └── bench_module.rs

├── examples/

│ ├── simple.rs

│ └── multi-file-example/

│ ├── main.rs

│ └── ex_module.rs

└── tests/

├── some-integration-tests.rs

└── multi-file-test/

├── main.rs

└── test_module.rs

dependencies

- Cargo.toml is about describing your dependencies in a broad sense, and is written by you.

- Cargo.lock contains exact information about your dependencies (including transitive dependencies), and is automatically contained by Cargo and should not be manually edited.

tests

Cargo can run your tests with the cargo test command. Cargo looks for tests to run in two places: in each of your src files and any tests in tests/. Tests in your src files should be unit tests and documentation tests. Tests in tests/ should be integration-style tests. As such, you’ll need to import your crates into the files in tests.

build

Cargo stores the output of a build into the “target” directory. By default, this is the directory named target in the root of your workspace. To change the location, you can set the CARGO_TARGET_DIR environment variable, the build.target-dir config value, or the --target-dir command-line flag.

The directory layout depends on whether or not you are using the --target flag to build for a specific platform. If --target is not specified, Cargo runs in a mode where it builds for the host architecture. The output goes into the root of the target directory, with each profile stored in a separate subdirectory:

Directory Description target/debug/ Contains output for the dev profile. target/release/ Contains output for the release profile (with the --release option). target/foo/ Contains build output for the foo profile (with the --profile=foo option).

For historical reasons, the dev and test profiles are stored in the debug directory, and the release and bench profiles are stored in the release directory. User-defined profiles are stored in a directory with the same name as the profile.

When building for another target with --target, the output is placed in a directory with the name of the target:

directories

Cargo caches data in the following directory structure:

/home/$USER/.cargo

├── bin

│ ├── cargo

│ ├── cargo-clippy

│ ├── cargo-fmt

│ ├── cargo-miri

│ ├── clippy-driver

│ ├── rls

│ ├── rust-analyzer

│ ├── rustc

│ ├── rustdoc

│ ├── rustfmt

│ ├── rust-gdb

│ ├── rust-gdbgui

│ ├── rust-lldb

│ ├── rustup

│ └── ssd-benchmark

├── env

├── git

│ ├── CACHEDIR.TAG

│ ├── checkouts

│ │ ├── application-services-99bb257f08384f94

│ │ │ └── c51b635

│ │ │ ├── automation

│ │ │ │ ├── cargo-update-pr.py

...

│ ├── db

│ │ ├── application-services-99bb257f08384f94

...

| registry

│ ├──cache

│ └── index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f

│ ├── adler-1.0.2.crate

│ ├── ahash-0.4.7.crate

│ ├── aho-corasick-0.7.18.crate

│ ├── alsa-0.4.3.crate

│ ├── alsa-sys-0.3.1.crate

│ ├── anyhow-1.0.57.crate

...

└── src

└── index.crates.io-6f17d22bba15001f

├── adler-1.0.2

│ ├── benches

│ │ └── bench.rs

│ ├── Cargo.toml

│ ├── Cargo.toml.orig

│ ├── CHANGELOG.md

│ ├── LICENSE-0BSD

│ ├── LICENSE-APACHE

│ ├── LICENSE-MIT

│ ├── README.md

│ ├── RELEASE_PROCESS.md

│ └── src

│ ├── algo.rs

│ └── lib.rs

This can make the requirements on the home drive very large.

du -h ~/.cargo ... 1.5G .cargo/

IDEs

Trialing the VisualStudio code IDE[47].

VisualStudio

VisualStudio IDEmay be installed on Debian/Ubuntu Linux.

- download VisualStudio for Debian 12[48]

- prequisites:

sudo apt install git

- install

sudo apt install ./code_1.80.2-1690491597_amd64.deb

The getting started document link[49]

https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/?dv=linux64_deb

The VisualStudio IDE is called code and can be launched from an XTerm via

code

Here is the explanation for the rust language

https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/languages/rust

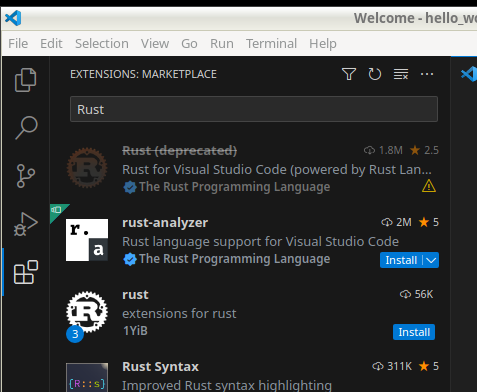

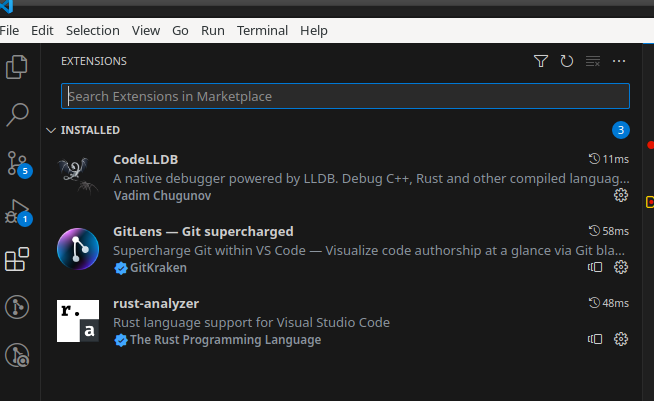

required extensions

For the Extension market place (Boxes) install

- rust-analyser

- CodeLLDB

cargo watch

Watches and runs when changes are made to cargo project. Very useful.

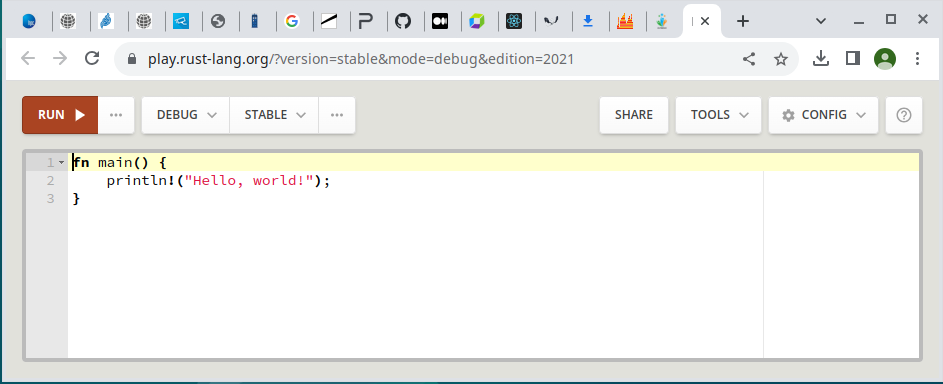

rust playground

The online playground IDE is very useful for testing and providing examples to others with its permalink facility:

syntax

When a name is forbidden because it is a reserved word (such as crate), either use a raw identifier (r#crate) or use a trailing underscore (crate_). Don't misspell the word (krate).

🚩 Note: a leading _ in a variable name is a statement that the variable does not need to be referenced.

rust style[50]

- snake_case for variable, functions, attributes et al.[51]

- function and method names

- local variables

- macro names

- constants (consts and immutable statics) - shall be SCREAMING_SNAKE_CASE.

- CamelCase [52]T

- Struct

- Types

- Enum variants

comments[53]

Use inline comments // instead of block comments /* .... */

Documentation comments /// for markdown[54][55]

rust semantics

attributes[56]

attributes are declarative tags placed above function definitions, modules, items, etc. They provide additional information or alter the behaviour of the code. Attributes in Rust start with a hashtag (#) and are placed inside square brackets ([]). For instance, an attribute could look like this: #[attribute].

Attributes can be classified into the following kinds:

- Built-in attributes

- Macro attributes

- Derive macro helper attributes

- Tool attributes

macro[57]

The term macro refers to a family of features in Rust: declarative macros with macro_rules! and three kinds of procedural macros:

- Custom #[derive] macros that specify code added with the derive attribute used on structs and enums

- Attribute-like macros that define custom attributes usable on any item

- Function-like macros that look like function calls but operate on the tokens specified as their argument

println

The println!, print! macros emits formatted string to stdout while eprint! and eprintln! output to stderr, and the macro format! writes formatted test to String, while the write! and writeln! macros emit the formatted string to a stream.

std::fmt contains many traits which govern the display of text:

- fmt:Debug uses the {:?} marker

- fmt:Display uses the {} marker.

Implementing the fmt::Display trait automatically implements the ToString trait which allows us to convert the type to String.

- Formatted Print[58]

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/56485167/how-to-format-a-byte-into-a-2-digit-hex-string-in-rust

- https://play.rust-lang.org/?version=stable&mode=debug&edition=2018&gist=fae66e4c050d1a343aa99881d91d2aad

fn main() {

println!("{:#01x}", 10);

println!("{:#02x}", 10);

println!("{:#03x}", 10);

println!("{:#04x}", 10);

println!("{:#05x}", 10);

println!("{:#06x}", 10);

}

- Prints:

0xa 0xa 0xa 0x0a 0x00a 0x000a

interpolation

Recall that String interpolation is performed by the format! (macro).

format!("Hello"); // => "Hello"

format!("Hello, {}!", "world"); // => "Hello, world!"

format!("The number is {}", 1); // => "The number is 1"

format!("{:?}", (3, 4)); // => "(3, 4)"

format!("{value}", value=4); // => "4"

let people = "Rustaceans";

format!("Hello {people}!"); // => "Hello Rustaceans!"

format!("{} {}", 1, 2); // => "1 2"

format!("{:04}", 42); // => "0042" with leading zeros

format!("{:#?}", (100, 200)); // => "(

// 100,

// 200,

// )"

positional parameters

Each formatting argument is allowed to specify which value argument it’s referencing, and if omitted it is assumed to be “the next argument”. For example, the format string {} {} {} would take three parameters, and they would be formatted in the same order as they’re given. The format string {2} {1} {0}, however, would format arguments in reverse order.

named parameters

Rust itself does not have a Python-like equivalent of named parameters to a function, but the format! macro is a syntax extension that allows it to leverage named parameters. Named parameters are listed at the end of the argument list and have the syntax:

identifier '=' expression

For example, the following format! expressions all use named arguments:

format!("{argument}", argument = "test"); // => "test"

format!("{name} {}", 1, name = 2); // => "2 1"

format!("{a} {c} {b}", a="a", b='b', c=3); // => "a 3 b"

If a named parameter does not appear in the argument list, format! will reference a variable with that name in the current scope.

formatting parameters[59]

Each argument being formatted can be transformed by a number of formatting parameters.

- width

// All of these print "Hello x !"

println!("Hello {:5}!", "x");

println!("Hello {:1$}!", "x", 5);

println!("Hello {1:0$}!", 5, "x");

println!("Hello {:width$}!", "x", width = 5);

let width = 5;

println!("Hello {:width$}!", "x");

- fill/alignment

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:<5}!", "x"), "Hello x !");

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:-<5}!", "x"), "Hello x----!");

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:^5}!", "x"), "Hello x !");

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:>5}!", "x"), "Hello x!");

- [fill]< - the argument is left-aligned in width columns

- [fill]^ - the argument is center-aligned in width columns

- [fill]> - the argument is right-aligned in width columns

- Sign/#/0

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:+}!", 5), "Hello +5!");

assert_eq!(format!("{:#x}!", 27), "0x1b!");

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:05}!", 5), "Hello 00005!");

assert_eq!(format!("Hello {:05}!", -5), "Hello -0005!");

assert_eq!(format!("{:#010x}!", 27), "0x0000001b!");

These are all flags altering the behavior of the formatter.

See https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/fmt/ for full details.

Types[60]

Primitives[61] include:

- scalar

- bool

- unit type ()

- arrays[62]

scalar

| numeric | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| u8 | u16 | u32 | u64 | u128 |

| i8 | i16 | i32 | i64 | i128 |

| usize | ... architecture dependent | |||

| isize | ... architecture dependent | |||

| f32 | f64 | |||

| character | ||||

| char | ||||

| boolean | ||||

| bool | ||||

tuple

let tuple = ( 1, 2.2, 'a', "string", (1,'b'));

println!("{:?}",tuple);

println!("{:#?}",tuple);}

- output

(1, 2.2, 'a', "string", (1, 'b'))

(

1,

2.2,

'a',

"string",

(

1,

'b',

),

)

array

An array is a fixed-size sequence of N elements of type T. The array type is written as [T; N]. The size is a constant expression that evaluates to a usize.

Examples:

// A stack-allocated array let array: [i32; 3] = [1, 2, 3]; // A heap-allocated array, coerced to a slice let boxed_array: Box<[i32]> = Box::new([1, 2, 3]); All elements of arrays are always initialized, and access to an array is always bounds-checked in safe methods and operators.

str

str: a stack allocated UTF-8 string, which can be borrowed as &str and sometimes &’static str, but can’t be moved[63]

String

String: a heap allocated UTF-8 string, which can be borrow as &String and &str, and can be moved[63].

let x: String = "abcdef";

slice

A slice is a dynamically sized type representing a 'view' into a sequence of elements of type T. The slice type is written as [T].

Slice types are generally used through pointer types. For example:

&[T]: a 'shared slice', often just called a 'slice'. It doesn't own the data it points to; it borrows it. &mut [T]: a 'mutable slice'. It mutably borrows the data it points to. Box<[T]>: a 'boxed slice'

Examples:

// A heap-allocated array, coerced to a slice let boxed_array: Box<[i32]> = Box::new([1, 2, 3]); // A (shared) slice into an array let slice: &[i32] = &boxed_array[..]; All elements of slices are always initialized, and access to a slice is always bounds-checked in safe methods and operators.

size

use std::mem::size_of;

use std::mem::size_of_val;

fn main() {

let x: char = 'a';

println!("{}",size_of::<char>());

println!("{}",size_of_val::<char>(&x));

}

pointer[64]

let my_num: i32 = 10; let my_num_ptr: *const i32 = &my_num; let mut my_speed: i32 = 88; let my_speed_ptr: *mut i32 = &mut my_speed; To get a pointer to a boxed value, dereference the box: let my_num: Box<i32> = Box::new(10); let my_num_ptr: *const i32 = &*my_num; let mut my_speed: Box<i32> = Box::new(88); let my_speed_ptr: *mut i32 = &mut *my_speed;

reference[65]

A reference represents a borrow of some owned value. You can get one by using the & or &mut operators on a value, or by using a ref or ref mut pattern.

For those familiar with pointers, a reference is just a pointer that is assumed to be aligned, not null, and pointing to memory containing a valid value of T - for example, &bool can only point to an allocation containing the integer values 1 (true) or 0 (false), but creating a &bool that points to an allocation containing the value 3 causes undefined behaviour. In fact, Option<&T> has the same memory representation as a nullable but aligned pointer, and can be passed across FFI boundaries as such.

In most cases, references can be used much like the original value. Field access, method calling, and indexing work the same (save for mutability rules, of course). In addition, the comparison operators transparently defer to the referent’s implementation, allowing references to be compared the same as owned values.

References have a lifetime attached to them, which represents the scope for which the borrow is valid. A lifetime is said to “outlive” another one if its representative scope is as long or longer than the other. The 'static lifetime is the longest lifetime, which represents the total life of the program. For example, string literals have a 'static lifetime because the text data is embedded into the binary of the program, rather than in an allocation that needs to be dynamically managed.

&mut T references can be freely coerced into &T references with the same referent type, and references with longer lifetimes can be freely coerced into references with shorter ones.

Reference equality by address, instead of comparing the values pointed to, is accomplished via implicit reference-pointer coercion and raw pointer equality via ptr::eq, while PartialEq compares values.

use std::ptr; let five = 5; let other_five = 5; let five_ref = &five; let same_five_ref = &five; let other_five_ref = &other_five; assert!(five_ref == same_five_ref); assert!(five_ref == other_five_ref); assert!(ptr::eq(five_ref, same_five_ref)); assert!(!ptr::eq(five_ref, other_five_ref));

custom types[66]

- struct[67]

struct Person {

name: String,

age: u8,

}

- enum[68]

enum WebEvent {

// An `enum` variant may either be `unit-like`,

PageLoad,

PageUnload,

// like tuple structs,

KeyPress(char),

Paste(String),

// or c-like structures.

Click { x: i64, y: i64 },

}

// A function which takes a `WebEvent` enum as an argument and

// returns nothing.

fn inspect(event: WebEvent) {

match event {

WebEvent::PageLoad => println!("page loaded"),

WebEvent::PageUnload => println!("page unloaded"),

// Destructure `c` from inside the `enum` variant.

WebEvent::KeyPress(c) => println!("pressed '{}'.", c),

WebEvent::Paste(s) => println!("pasted \"{}\".", s),

// Destructure `Click` into `x` and `y`.

WebEvent::Click { x, y } => {

println!("clicked at x={}, y={}.", x, y);

},

}

}

- union[69]

union MyUnion {

f1: u32,

f2: f32,

}

constants

- constants[70]

static LANGUAGE: &str = "Rust"; const THRESHOLD: i32 = 10;

literals[71]

numerical

An integer literal expression consists of a single INTEGER_LITERAL token.

If the token has a suffix, the suffix must be the name of one of the primitive integer types: u8, i8, u16, i16, u32, i32, u64, i64, u128, i128, usize, or isize, and the expression has that type.

If the token has no suffix, the expression's type is determined by type inference:

If an integer type can be uniquely determined from the surrounding program context, the expression has that type.

If the program context under-constrains the type, it defaults to the signed 32-bit integer i32.

If the program context over-constrains the type, it is considered a static type error.

The value of the float expression is determined from the string representation of the token as follows:

Any suffix is removed from the string.

Any underscores are removed from the string.

Then the string is converted to the expression's type as if by f32::from_str or f64::from_str.

let x = 255_u16; let x = 0xff + 0o77 + 0b1111_1010 + l_024; let x = 0.01_f64; let x = 1.312E+03_f32;

generic types

In struct

struct Point<T> {

x: T,

y: T,

}

fn main() {

let integer = Point { x: 5, y: 10 };

let float = Point { x: 1.0, y: 4.0 };

}

In enum

enum Option<T> {

Some(T),

None,

}

In functions

struct Point<X1, Y1> {

x: X1,

y: Y1,

}

impl<X1, Y1> Point<X1, Y1> {

fn mixup<X2, Y2>(self, other: Point<X2, Y2>) -> Point<X1, Y2> {

Point {

x: self.x,

y: other.y,

}

}

}

fn main() {

let p1 = Point { x: 5, y: 10.4 };

let p2 = Point { x: "Hello", y: 'c' };

let p3 = p1.mixup(p2);

println!("p3.x = {}, p3.y = {}", p3.x, p3.y);

}

type_name

Obtaining type information[72]

use std::any::type_name;

fn type_of<T>(_: T) -> &'static str {

type_name::<T>()

}

fn main() {

let message: &str = "Hello world!";

println!("{} {}", message,type_of(message));

}

- result

Hello world! &str 10 i32

See also the Any Trait<fref>rust Any Trait https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/any/trait.Any.html</ref>

variables[73]

Variables[74] are a component of a stack frame, either a named function parameter, an anonymous temporary, or a named local variable. A local variable holds a value directly, allocated within a stack's memory. and the value is part of the stack-frame.

Local variables are immutable unless declared otherwise:

- immutable

let _immutable_binding = 1;

- mutable

let mut mutable_binding = 1;

Function parameters are immutable unless declared mutable too.

The entire stack frame containing variables is allocated in an uninitialized state. Subsequent statments within the may or may not initialize a local variable.

Diagnostics

// Ok

mutable_binding += 1;

println!("After mutation: {}", mutable_binding);

// Error! Cannot assign a new value to an immutable variable

_immutable_binding += 1;

- variables may be initialized after they are declared[75] which is used in if/else blocks to initialize immutable variables.

scope[76]

- variables have scope i.e. they belong to a block and are not visible outside that block

- out-block variables may be shadowed' inner variables shadow outer variables (of the same name).

- freezing an immutable reference to data freezes the data; said data cannot be modified until the immutable reference goes out of scope.[77]

casting

Rust provides 'no implicit type conversion.

Primitive types may be cast to other primitive types[78]

let decimal = 65.4321_f32;

// Error! No implicit conversion

let integer: u8 = decimal;

// FIXME ^ Comment out this line

// Explicit conversion

let integer = decimal as u8;

let character = integer as char;

suffixed literal

- Literal may be cast to a type by a suffix[79].

// Suffixed literals, their types are known at initialization

let x = 1u8;

let y = 2u32;

let z = 3f32;

- inference[80]

The compiler can make inference about types (after an assignment), and from then on it will enforce that type inference.

fn main() {

// Because of the annotation, the compiler knows that `elem` has type u8.

let elem = 5u8;

// Create an empty vector (a growable array).

let mut vec = Vec::new();

// At this point the compiler doesn't know the exact type of `vec`, it

// just knows that it's a vector of something (`Vec<_>`).

// Insert `elem` in the vector.

vec.push(elem);

// Aha! Now the compiler knows that `vec` is a vector of `u8`s (`Vec<u8>`)

// TODO ^ Try commenting out the `vec.push(elem)` line

println!("{:?}", vec);

}

- alias; a type may be aliased[81] via a CamelCase name e.g.

type NanoSecond = u64;

conversion

- conversion[82]; rust supports type conversion, even for struct and enum, via Traits From[83] and Into[83]

- string conversion and parsing [84]

Algebraic features

statistics[85]

- https://rust-lang-nursery.github.io/rust-cookbook/science/mathematics/statistics.html

- https://docs.rs/statistical/latest/statistical/

nalgebra[86]/

matrices

Linear Algebra is supported by Matrix[87] and Complex types.

- https://docs.rs/matrix/latest/matrix/index.html

- https://rust-lang-nursery.github.io/rust-cookbook/science/mathematics/linear_algebra.html

complex numbers[88]

operators[89]

Operators[90] are described

- markup https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/appendix-02-operators.html

- names https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/ops/index.html

Operator overloading[91] is also provided, e.g. for Complex numbers.

Trait[92]

The following traits are implemented for all &T, regardless of the type of its referent:

- Copy

- Clone (Note that this will not defer to T’s Clone implementation if it exists!)

- Deref

- Borrow

- fmt::Pointer

&mut T references get all of the above except Copy and Clone (to prevent creating multiple simultaneous mutable borrows), plus the following, regardless of the type of its referent:

- DerefMut

- BorrowMut

The following traits are implemented on &T references if the underlying T also implements that trait:

- All the traits in std::fmt except fmt::Pointer (which is implemented regardless of the type of its referent) and fmt::Write

- PartialOrd

- Ord

- PartialEq

- Eq

- AsRef

- Fn (in addition, &T references get FnMut and FnOnce if T: Fn)

- Hash

- ToSocketAddrs

- Send (&T references also require T: Sync)

- Sync

&mut T references get all of the above except ToSocketAddrs, plus the following, if T implements that trait:

- AsMut

- FnMut (in addition, &mut T references get FnOnce if T: FnMut) fmt::Write

- Iterator

- DoubleEndedIterator

- ExactSizeIterator

- FusedIterator

- TrustedLen

- io::Write

- Read

- Seek

- BufRead

Note that due to method call deref coercion, simply calling a trait method will act like they work on references as well as they do on owned values! The implementations described here are meant for generic contexts, where the final type T is a type parameter or otherwise not locally known.

control flow

LoopExpression :

LoopLabel? (

InfiniteLoopExpression

| PredicateLoopExpression

| PredicatePatternLoopExpression

| IteratorLoopExpression

| LabelBlockExpression

)

'outer: loop {

while true {

break 'outer;

}

}

let result = 'block: {

do_thing();

if condition_not_met() {

break 'block 1;

}

do_next_thing();

if condition_not_met() {

break 'block 2;

}

do_last_thing();

3

};

When associated with a loop, a break expression may be used to return a value from that loop, via one of the forms break EXPR or break 'label EXPR, where EXPR is an expression whose result is returned from the loop. For example:

let (mut a, mut b) = (1, 1);

let result = loop {

if b > 10 {

break b;

}

let c = a + b;

a = b;

b = c;

};

// first number in Fibonacci sequence over 10:

assert_eq!(result, 13);

- while[95]

let mut i = 0;

while i < 10 {

println!("hello");

i = i + 1;

}

<pre>

<pre>

let mut vals = vec![2, 3, 1, 2, 2];

while let Some(v @ 1) | Some(v @ 2) = vals.pop() {

// Prints 2, 2, then 1

println!("{}", v);

}

- for

let v = &["apples", "cake", "coffee"];

for text in v {

println!("I like {}.", text);

}

- for range[96] (See also range expression.)

let mut sum = 0;

// note this will run 11 times with n =1 ... n =10

for n in 1..11 {

sum += n;

}

- match[97]

// tuples

match triple {

// Destructure the second and third elements

(0, y, z) => println!("First is `0`, `y` is {:?}, and `z` is {:?}", y, z),

(1, ..) => println!("First is `1` and the rest doesn't matter"),

(.., 2) => println!("last is `2` and the rest doesn't matter"),

(3, .., 4) => println!("First is `3`, last is `4`, and the rest doesn't matter"),

// `..` can be used to ignore the rest of the tuple

_ => println!("It doesn't matter what they are"),

// `_` means don't bind the value to a variable

}

match array {

// Binds the second and the third elements to the respective variables

[0, second, third] =>

println!("array[0] = 0, array[1] = {}, array[2] = {}", second, third),

// Single values can be ignored with _

[1, _, third] => println!(

"array[0] = 1, array[2] = {} and array[1] was ignored",

third

),

match color {

Color::Red => println!("The color is Red!"),

Color::Blue => println!("The color is Blue!"),

Color::Green => println!("The color is Green!"),

Color::RGB(r, g, b) =>

match reference {

// If `reference` is pattern matched against `&val`, it results

// in a comparison like:

// `&i32`

// `&val`

// ^ We see that if the matching `&`s are dropped, then the `i32`

// should be assigned to `val`.

&val => println!("Got a value via destructuring: {:?}", val),

}

// To avoid the `&`, you dereference before matching.

match *reference {

val => println!("Got a value via dereferencing: {:?}", val),

}

// struct

match foo {

Foo { x: (1, b), y } => println!("First of x is 1, b = {}, y = {} ", b, y),

// you can destructure structs and rename the variables,

// the order is not important

Foo { y: 2, x: i } => println!("y is 2, i = {:?}", i),

// and you can also ignore some variables:

Foo { y, .. } => println!("y = {}, we don't care about x", y),

// this will give an error: pattern does not mention field `x`

//Foo { y } => println!("y = {}", y),

}

- match guards

match temperature {

Temperature::Celsius(t) if t > 30 => println!("{}C is above 30 Celsius", t),

// The `if condition` part ^ is a guard

Temperature::Celsius(t) => println!("{}C is below 30 Celsius", t),

Temperature::Fahrenheit(t) if t > 86 => println!("{}F is above 86 Fahrenheit", t),

Temperature::Fahrenheit(t) => println!("{}F is below 86 Fahrenheit", t),

}

- match binding[98]

match age() {

0 => println!("I haven't celebrated my first birthday yet"),

// Could `match` 1 ..= 12 directly but then what age

// would the child be? Instead, bind to `n` for the

// sequence of 1 ..= 12. Now the age can be reported.

n @ 1 ..= 12 => println!("I'm a child of age {:?}", n),

n @ 13 ..= 19 => println!("I'm a teen of age {:?}", n),

// Nothing bound. Return the result.

n => println!("I'm an old person of age {:?}", n),

}

range expression[102]

| Production | Syntax | Type | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| RangeExpr | start..end | std::ops::Range | start ≤ x < end |

| RangeFromExpr | start.. | std::ops::RangeFrom | start ≤ x |

| RangeToExpr | ..end | std::ops::RangeTo | x < end |

| RangeFullExpr | .. | std::ops::RangeFul | - |

| RangeInclusiveExpr | start..=end | std::ops::RangeInclusive | start ≤ x ≤ end |

| RangeToInclusiveExpr | ..=end | std::ops::RangeToInclusive | x ≤ end |

functions[103]

// Function that returns a boolean value

fn is_divisible_by(lhs: u32, rhs: u32) -> bool {

// Corner case, early return

if rhs == 0 {

return false;

}

// This is an expression, the `return` keyword is not necessary here

lhs % rhs == 0

}

- associated functions[104]

struct Point {

x: f64,

y: f64,

}

// Implementation block, all `Point` associated functions & methods go in here

impl Point {

// This is an "associated function" because this function is associated with

// a particular type, that is, Point.

//

// Associated functions don't need to be called with an instance.

// These functions are generally used like constructors.

fn origin() -> Point {

Point { x: 0.0, y: 0.0 }

}

// Another associated function, taking two arguments:

fn new(x: f64, y: f64) -> Point {

Point { x: x, y: y }

}

}

- methods[104]

impl Rectangle {

// This is a method

// `&self` is sugar for `self: &Self`, where `Self` is the type of the

// caller object. In this case `Self` = `Rectangle`

fn area(&self) -> f64 {

// `self` gives access to the struct fields via the dot operator

let Point { x: x1, y: y1 } = self.p1;

let Point { x: x2, y: y2 } = self.p2;

// `abs` is a `f64` method that returns the absolute value of the

// caller

((x1 - x2) * (y1 - y2)).abs()

}

fn perimeter(&self) -> f64 {

let Point { x: x1, y: y1 } = self.p1;

let Point { x: x2, y: y2 } = self.p2;

2.0 * ((x1 - x2).abs() + (y1 - y2).abs())

}

// This method requires the caller object to be mutable

// `&mut self` desugars to `self: &mut Self`

fn translate(&mut self, x: f64, y: f64) {

self.p1.x += x;

self.p2.x += x;

self.p1.y += y;

self.p2.y += y;

}

}

- closure[105] | |

fn main() {

let outer_var = 42;

// A regular function can't refer to variables in the enclosing environment

//fn function(i: i32) -> i32 { i + outer_var }

// TODO: uncomment the line above and see the compiler error. The compiler

// suggests that we define a closure instead.

// Closures are anonymous, here we are binding them to references

// Annotation is identical to function annotation but is optional

// as are the `{}` wrapping the body. These nameless functions

// are assigned to appropriately named variables.

let closure_annotated = |i: i32| -> i32 { i + outer_var };

let closure_inferred = |i | i + outer_var ;

use rand; // 0.8.4

fn main() {

let foo;

if rand::random::<bool>() {

foo = "Hello, world!";

} else {

diverge();

}

println!("{foo}");

}

fn diverge() {

panic!("Crash!");

}

We declare a variable foo, but we only initialize it in one branch of the if expression. This fails to compile with the following error:

error[E0381]: borrow of possibly-uninitialized variable: `foo`

--> src/main.rs:10:15

|

10 | println!("{foo}");

| ^^^^^ use of possibly-uninitialized `foo`

However, if we change the definition of our diverge function like this:

fn diverge() -> ! {

panic!("Crash!");

}

then the code successfully compiles. The compiler knows that if the else branch is taken, it will never reach the println! because diverge() diverges. Therefore, it's not an error that the else branch doesn't initialize foo.

closure expression[109]

A closure expression denotes a function that maps a list of parameters onto the expression that follows the parameters. Just like a let binding, the closure parameters are irrefutable patterns, whose type annotation is optional and will be inferred from context if not given. Each closure expression has a unique, anonymous type.

Significantly, closure expressions capture their environment, which regular function definitions do not. Without the move keyword, the closure expression infers how it captures each variable from its environment, preferring to capture by shared reference, effectively borrowing all outer variables mentioned inside the closure's body. If needed the compiler will infer that instead mutable references should be taken, or that the values should be moved or copied (depending on their type) from the environment. A closure can be forced to capture its environment by copying or moving values by prefixing it with the move keyword. This is often used to ensure that the closure's lifetime is 'static.

Syntax ClosureExpression : move? ( || | | ClosureParameters? | ) (Expression | -> TypeNoBounds BlockExpression) ClosureParameters : ClosureParam (, ClosureParam)* ,? ClosureParam : OuterAttribute* PatternNoTopAlt ( : Type )?

E.g.

fn ten_times<F>(f: F) where F: Fn(i32) {

for index in 0..10 {

f(index);

}

}

ten_times(|j| println!("hello, {}", j));

// With type annotations

ten_times(|j: i32| -> () { println!("hello, {}", j) });

let word = "konnichiwa".to_owned();

ten_times(move |j| println!("{}, {}", word, j));

namespaces[110]

A namespace is a logical grouping of declared names. Names are segregated into separate namespaces based on the kind of entity the name refers to. Namespaces allow the occurrence of a name in one namespace to not conflict with the same name in another namespace.

Within a namespace, names are organized in a hierarchy, where each level of the hierarchy has its own collection of named entities.

There are several different namespaces that each contain different kinds of entities. The usage of a name will look for the declaration of that name in different namespaces, based on the context.

- Type Namespace containing

- Module declarations

- External crate declarations

- External crate prelude items

- Struct, union, enum, enum variant declarations

- Trait item declarations

- Type aliases

- Associated type declarations

- Built-in types:

- boolean,

- numeric,

- and textual

- Generic type parameters

- Self type

- Tool attribute modules

- Value Namespace

- Function declarations

- Constant item declarations

- Static item declarations

- Struct constructors

- Enum variant constructors

- Self constructors

- Generic const parameters

- Associated const declarations

- Associated function declarations

- Local bindings

- let,

- if let,

- while let,

- for,

- match arms,

- function parameters,

- closure parameters

- Captured closure variables

- Macro Namespace

- macro_rules declarations

- Built-in attributes

- Tool attributes

- Function-like procedural macros

- Derive macros

- Derive macro helpers

- Attribute macros

- Lifetime Namespace

- Generic lifetime parameters

- Label Namespace

- Loop labels

- Block labels

A path[111] is a sequence of one or more path segments separated by a namespace qualifier (::) e.g. std::io

use std::io::{self, Write};

mod m {

#[clippy::cyclomatic_complexity = "0"]

pub (in super) fn f1() {}

}

The :: token is required before the opening < for generic arguments to avoid ambiguity with the less-than operator. This is colloquially known as "turbofish" syntax e.g.

(0..10).collect::<Vec<_>>(); Vec::<u8>::with_capacity(1024);

Paths starting with :: are considered to be global paths where the segments of the path start being resolved from a place which differs based on edition. Each identifier in the path must resolve to an item.

pub fn foo() {

// In the 2018 edition, this accesses `std` via the extern prelude.

// In the 2015 edition, this accesses `std` via the crate root.

let now = ::std::time::Instant::now();

println!("{:?}", now);

}

'self resolves the path relative to the current module. self can only be used as the first segment, without a preceding ::.

fn foo() {}

fn bar() {

self::foo();

}

Self, with a capital "S", is used to refer to the implementing type within traits and implementations. Self can only be used as the first segment, without a preceding ::.

trait T {

type Item;

const C: i32;

// `Self` will be whatever type that implements `T`.

fn new() -> Self;

// `Self::Item` will be the type alias in the implementation.

fn f(&self) -> Self::Item;

}

struct S;

impl T for S {

type Item = i32;

const C: i32 = 9;

fn new() -> Self { // `Self` is the type `S`.

S

}

fn f(&self) -> Self::Item { // `Self::Item` is the type `i32`.

Self::C // `Self::C` is the constant value `9`.

}

}

super in a path resolves to the parent module. It may only be used in leading segments of the path, possibly after an initial self segment.

mod a {

pub fn foo() {}

}

mod b {

pub fn foo() {

super::a::foo(); // call a's foo function

}

}

super may be repeated several times after the first super or self to refer to ancestor modules.

mod a {

fn foo() {}

mod b {

mod c {

fn foo() {

super::super::foo(); // call a's foo function

self::super::super::foo(); // call a's foo function

}

}

}

}

crate resolves the path relative to the current crate. crate can only be used as the first segment, without a preceding ::.

fn foo() {}

mod a {

fn bar() {

crate::foo();

}

}

$crate is only used within macro transcribers, and can only be used as the first segment, without a preceding ::. $crate will expand to a path to access items from the top level of the crate where the macro is defined, regardless of which crate the macro is invoked.

pub fn increment(x: u32) -> u32 {

x + 1

}

#[macro_export]

macro_rules! inc {

($x:expr) => ( $crate::increment($x) )

}

cannonical path

Items defined in a module or implementation have a canonical path that corresponds to where within its crate it is defined. All other paths to these items are aliases. The canonical path is defined as a path prefix appended by the path segment the item itself defines.

Implementations and use declarations do not have canonical paths, although the items that implementations define do have them. Items defined in block expressions do not have canonical paths. Items defined in a module that does not have a canonical path do not have a canonical path. Associated items defined in an implementation that refers to an item without a canonical path, e.g. as the implementing type, the trait being implemented, a type parameter or bound on a type parameter, do not have canonical paths.

The path prefix for modules is the canonical path to that module. For bare implementations, it is the canonical path of the item being implemented surrounded by angle (<>) brackets. For trait implementations, it is the canonical path of the item being implemented followed by as followed by the canonical path to the trait all surrounded in angle (<>) brackets.

The canonical path is only meaningful within a given crate. There is no global namespace across crates; an item's canonical path merely identifies it within the crate.

// Comments show the canonical path of the item.

mod a { // crate::a

pub struct Struct; // crate::a::Struct

pub trait Trait { // crate::a::Trait

fn f(&self); // crate::a::Trait::f

}

impl Trait for Struct {

fn f(&self) {} // <crate::a::Struct as crate::a::Trait>::f

}

impl Struct {

fn g(&self) {} // <crate::a::Struct>::g

}

}

mod without { // crate::without

fn canonicals() { // crate::without::canonicals

struct OtherStruct; // None

trait OtherTrait { // None

fn g(&self); // None

}

impl OtherTrait for OtherStruct {

fn g(&self) {} // None

}

impl OtherTrait for crate::a::Struct {

fn g(&self) {} // None

}

impl crate::a::Trait for OtherStruct {

fn f(&self) {} // None

}

}

}

prelude[112]

A prelude is a collection of names tgat are automatically brought into scope of every module in a crate. These are not part of the crate and cannot be referred by the crate because they are not members of that crate module

There are several different preludes:

- Standard library prelude

- Extern prelude

- Language prelude

- macro_use prelude

- Tool prelude

visibility[113]

Visibility :

- public

- pub

- pub ( crate )

- pub ( self )

- pub ( super )

- pub ( in SimplePath )

pub mod outer_mod {

pub mod inner_mod {

// This function is visible within `outer_mod`

pub(in crate::outer_mod) fn outer_mod_visible_fn() {}

// Same as above, this is only valid in the 2015 edition.

pub(in outer_mod) fn outer_mod_visible_fn_2015() {}

// This function is visible to the entire crate

pub(crate) fn crate_visible_fn() {}

// This function is visible within `outer_mod`

pub(super) fn super_mod_visible_fn() {

// This function is visible since we're in the same `mod`

inner_mod_visible_fn();

}

// This function is visible only within `inner_mod`,

// which is the same as leaving it private.

pub(self) fn inner_mod_visible_fn() {}

}

pub fn foo() {

inner_mod::outer_mod_visible_fn();

inner_mod::crate_visible_fn();

inner_mod::super_mod_visible_fn();

// This function is no longer visible since we're outside of `inner_mod`

// Error! `inner_mod_visible_fn` is private

//inner_mod::inner_mod_visible_fn();

}

}

- pub use

//rust allows publicly re-exporting items through a pub use directive. This allows the exported item to be used in the current module through the rules above.

pub use self::implementation::api;

mod implementation {

pub mod api {

pub fn f() {}

}

}

standard library

TO DO copy these across https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rust_(programming_language)

The std[114] crate provides the standard library features.

- macros [115] - which includes print![116] and println![117]

- box [118]

- vectors [119]

- string [120]

- option [121]

- result [122]

- panic [123]

- HashMap [124]

- HashSet[125]

- Rc[126]

- Arc[127]

- std::thread Threads[128]

- std::sync::mpsc::{Sender, Receiver} - Channels[129]

- std::path::Path - Path[130]

- std::fs::File - File[131]

- std::process::Command - ChildProcess[132]

- Pipe[133]

- std::fs file system operations[134]

ownership[135]

- ->String https://hermanradtke.com/2015/05/29/creating-a-rust-function-that-returns-string-or-str.html/

- fn ( String ) takes ownership of String

asm[136]

Rust supports the use of inline assembly.

use std::arch::asm;

// Multiply x by 6 using shifts and adds

let mut x: u64 = 4;

unsafe {

asm!(

"mov {tmp}, {x}",

"shl {tmp}, 1",

"shl {x}, 2",

"add {x}, {tmp}",

x = inout(reg) x,

tmp = out(reg) _,

);

}

assert_eq!(x, 4 * 6);

Possible uses:

- https://developer.arm.com/documentation/dui0473/m/arm-and-thumb-instructions/bkpt

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/INT_(x86_instruction)#:~:text=The%20INT3%20instruction%20is%20a,to%20set%20a%20code%20breakpoint.

error handling[137]

- ? from trait[138]

unsafety[139]

The rust compiler enforces safety via static analysis. Unsafe operations are those that can potentially violate the memory-safety guarantees of Rust's static semantics.

The following language level features cannot be used in the safe subset of Rust:

- Dereferencing a raw pointer.

- Reading or writing a mutable or external static variable.

- Accessing a field of a union, other than to assign to it.

- Calling an unsafe function (including an intrinsic or foreign function).

- Implementing an unsafe trait.

A block of code can be prefixed with the unsafe keyword, to permit calling unsafe functions or dereferencing raw pointers. By default, the body of an unsafe function is also considered to be an unsafe block; this can be changed by enabling the unsafe_op_in_unsafe_fn lint.

By putting operations into an unsafe block, the programmer states that they have taken care of satisfying the extra safety conditions of all operations inside that block.

An unsafe trait is a trait that comes with extra safety conditions that must be upheld by implementations of the trait. The unsafe trait should come with documentation explaining what those extra safety conditions are.

Such a trait must be prefixed with the keyword unsafe and can only be implemented by unsafe impl blocks.

not unsafe behavious

The Rust compiler does not consider the following behaviors unsafe, though a programmer may (should) find them undesirable, unexpected, or erroneous.

- Deadlocks

- Leaks of memory and other resources

- Exiting without calling destructors

- Exposing randomized base addresses through pointer leaks

- Integer overflow

If a program contains arithmetic overflow, the programmer has made an error. In the following discussion, we maintain a distinction between arithmetic overflow and wrapping arithmetic. The first is erroneous, while the second is intentional.

When the programmer has enabled debug_assert! assertions (for example, by enabling a non-optimized build), implementations must insert dynamic checks that panic on overflow. Other kinds of builds may result in panics or silently wrapped values on overflow, at the implementation's discretion.

In the case of implicitly-wrapped overflow, implementations must provide well-defined (even if still considered erroneous) results by using two's complement overflow conventions.

The integral types provide inherent methods to allow programmers explicitly to perform wrapping arithmetic. For example, i32::wrapping_add provides two's complement, wrapping addition.

The standard library also provides a Wrapping<T> newtype which ensures all standard arithmetic operations for T have wrapping semantics.

See RFC 560 for error conditions, rationale, and more details about integer overflow.

- Logic errors

Safe code may impose extra logical constraints that can be checked at neither compile-time nor runtime. If a program breaks such a constraint, the behavior may be unspecified but will not result in undefined behavior. This could include panics, incorrect results, aborts, and non-termination. The behavior may also differ between runs, builds, or kinds of build.

For example, implementing both Hash and Eq requires that values considered equal have equal hashes. Another example are data structures like BinaryHeap, BTreeMap, BTreeSet, HashMap and HashSet which describe constraints on the modification of their keys while they are in the data structure. Violating such constraints is not considered unsafe, yet the program is considered erroneous and its behavior unpredictable.

linkage[140]

TBD.

debugging[141]

Rust application can be debugged via the wrapper for gdb[142]

rust-gdb

GDB Commands are outlined:

Alternatively you may debug via #VisualStudio

Problem areas

- changing stack size https://www.reddit.com/r/rust/comments/872fc4/how_to_increase_the_stack_size/

variadic functions

numeric types

- https://lib.rs/crates/bnum

- https://docs.rs/num-bigint/latest/num_bigint/struct.BigInt.html

- https://docs.rs/num-bigint/latest/num_bigint/struct.BigUint.html

- https://lib.rs/crates/bigdecimal

- https://lib.rs/crates/ibig

- https://lib.rs/crates/fpdec

- https://lib.rs/crates/num-bigfloat

- https://lib.rs/crates/rust_decimal

- https://lib.rs/crates/num-traits

- https://lib.rs/crates/daisycalc

- https://lib.rs/crates/mathru

- https://lib.rs/crates/numbat-cli

- https://lib.rs/crates/rithm

- https://lib.rs/crates/scilib

- https://lib.rs/crates/maths-rs

- https://lib.rs/crates/dec

- https://lib.rs/crates/ode_solvers

- https://lib.rs/crates/ndrustfft

- https://lib.rs/crates/scientific

- https://lib.rs/crates/rpn-c

- https://lib.rs/crates/precise-calc

- https://lib.rs/crates/qalqulator

time

Well time will cause you problem until you understand the various packages:

- std::time - for instance and duration objects

- std::chrono - date/time manipulation

- rustix (Posix bindings) https://crates.io/crates/rustix

- embassy-time https://lib.rs/crates/embassy-time

... there are more.

use chrono::{Local,Utc, NaiveDateTime,DateTime};

use std::time::{Duration,Instant,SystemTime};

fn main() {

let _a = Utc;

let _b: Duration = Duration::new(0,0);

let _c = Instant::now();

/// instance of time features

let system_time = SystemTime::now();

let utc_date:DateTime<Utc> = system_time.into();

println!("sysTime=[{}]",utc_date);

/// proper time features

let local_time = Local::now(); // current date time

let time = local_time.timestamp(); // timestamp

let nano = local_time.timestamp_subsec_nanos();

let utc_time = local_time.naive_utc(); // utc time

println!("local=[{:?}] utc=[{:?}] timestamp=[{}]",local_time,utc_time,time);

}

The reference doc

crates

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf2

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf-extract

- https://crates.io/crates/mdbook-latex

- https://crates.io/crates/mdbook-pdf

- https://github.com/ralpha/pdf_signing

- lopdf https://crates.io/crates/lopdf

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf_cli

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf-create

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf_form

- pdfium wrapper https://crates.io/crates/pdfium-render

- https://crates.io/crates/pdf-writer

- pandoc wrapper https://crates.io/crates/rsmooth

- html -> pdf https://crates.io/crates/htop

- html -> pdf (uses headless chrome to do the conversion) https://crates.io/crates/html2pdf

- https://crates.io/crates/scannedpdf

- https://crates.io/crates/budgetinvoice

- markdown https://crates.io/crates/crowbook

- markdown https://crates.io/crates/p4d-mdproof

- extract data https://crates.io/crates/cephalon

- bindings https://crates.io/crates/qpdf

- chromium interaction https://crates.io/crates/chromiumoxide

- commic and ebook https://crates.io/crates/eloran

- embedded LaTexX engine https://crates.io/crates/tectonic

- pdf tools https://crates.io/crates/rpdf

- pdf library https://crates.io/crates/pdfdbg

modbus

graphics

- 2D https://docs.rs/piston2d-graphics/latest/graphics/

- Charts https://docs.rs/charts/latest/charts/

- charming https://github.com/yuankunzhang/charming

- https://crates.io/crates/rgb

- https://crates.io/crates/tiny-skia-path

- https://crates.io/crates/epaint

- https://crates.io/crates/kurbo

- https://crates.io/crates/zeno

- https://crates.io/crates/plotly

- https://crates.io/crates/robust

- https://crates.io/crates/raqote

- GPU https://crates.io/crates/gpu-alloc

- GPU https://crates.io/crates/pixels

- game api https://crates.io/crates/bevy

- image https://crates.io/crates/resize

- https://lib.rs/crates/async-graphql

- https://lib.rs/crates/gtk4

- https://lib.rs/crates/glib

- https://lib.rs/crates/map_3d

- https://lib.rs/crates/stroke

computer vision

benchmarks and profiling

- microbench https://lib.rs/crates/microbench

- benchmarking using flamegraphs and perf https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=D53T1Ejig1Q

- firestorm https://lib.rs/crates/firestorm

- inferno https://docs.rs/inferno/latest/inferno/

- getting started with flamegraphs https://access.redhat.com/documentation/en-us/red_hat_enterprise_linux/8/html/monitoring_and_managing_system_status_and_performance/getting-started-with-flamegraphs_monitoring-and-managing-system-status-and-performance

- flamegraphs https://www.brendangregg.com/flamegraphs.html

- tracing-flame https://lib.rs/crates/tracing-flame

- https://lib.rs/crates/tracy-client

- inferno https://docs.rs/inferno/latest/inferno/

- perf-event Linux kernel profiler

- iai-callgrind https://lib.rs/crates/iai-callgrind

- critereon https://lib.rs/crates/criterion

- tiny-bench https://lib.rs/crates/tiny-bench

- brunch https://lib.rs/crates/brunch

- countme allocated instances https://lib.rs/crates/countme

- metered https://crates.io/crates/metered-macro

- https://lib.rs/crates/dogstatsd

- gnup lot http://www.gnuplot.info/

- pyrosocpe mulit-language agents and server for visualisation with dadgerDB back end.

- profiling https://lib.rs/crates/profiling

- puffin https://lib.rs/crates/puffin

- counts https://lib.rs/crates/profiling

- https://lib.rs/crates/usdt

- dhatrs heap profiling https://lib.rs/crates/dhat

- self-meter https://crates.io/crates/self-meter

- self-meter-http https://crates.io/crates/self-meter-http

- prometheus

- metrics https://docs.rs/metrics/0.21.1/metrics/

- metrics-core https://docs.rs/metrics-core/latest/metrics_core/

GUI

GUI framework:

| name | production | compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| dixosus | ? | desktop and web |

| gtk-rs | yes | cross-platform |

| fltk-rs | yes | cross-platform |

| iced | no | cross-platform and web |

| relm | no | cross-platform |

| Azul | yes | cross-platform |

| egui | old | cross-platform |

| Tauri | yes | desktop and web |

| Slint | yes | crossplatorm and web (demo only/requires licence) |

| Druid | yes superceded by Xilim |

desktop and web |

| xilim | ? | desktop and web |

- GUI https://blog.logrocket.com/state-of-rust-gui-libraries/

- https://docs.rs/piston2d-graphics/latest/graphics/

- NativeWindowsGUI https://github.com/gabdube/native-windows-gui

- GTK https://gtk-rs.org/

- (web) egui https://crates.io/crates/egui

- https://docs.rs/nannou/0.18.1/nannou/

- slint https://madewithslint.com/

- (web) tauri https://tauri.app/

- druid (native) https://github.com/linebender/druid[143] superceeded by xilim.

- xilim https://github.com/linebender/xilem/ (supercedes druid)

- elm https://guide.elm-lang.org/architecture/

- dioxus (web,app, desktop) https://dioxuslabs.com/

findings

comparative performance

- language performance https://github.com/niklas-heer/speed-comparison

- https://benchmarksgame-team.pages.debian.net/benchmarksgame/box-plot-summary-charts.html

- rust vs C https://benchmarksgame-team.pages.debian.net/benchmarksgame/fastest/rust.html

- rust vs others Mandlebrot https://programming-language-benchmarks.vercel.app/problem/mandelbrot

training videos

- (excellent) start here for beginners by @zubiarfan https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpPEoZW5IiY

- https://www.rustadventure.dev/

- Traits and polymorphism https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHRNj5oubwc

- Borrow checker https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HwupNf9iCJk

- clone(), copy(), & , &, 'lifetimes mut https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TJTDTyNdJdY

- smart pointers https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CTTiaOo4cbY

- data science linfa https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mlcSpxicx-4

- AI rust https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FI-8L-hobDY

- Ok Error Result options https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f82wn-1DPas[145]

- rust macros https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IsCBibC0PZE

- testing & mocking rust https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8XaVlL3lObQ

- universal libraries https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uKlHwko36c4

- log observability parseable https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Eg_Keqt1I0

- SQLX https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v9fnBhzH5u8

- (excellent) introduction to web-application full stack using: axum tower tokio - Reinart Stropek https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DCpILwGas-M

- rust-web-app axum https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3cA_mk4vdWY

references

- ↑ rust language https://www.rust-lang.org/

- ↑ C++ https://cplusplus.com/

- ↑ rust cargo https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch01-03-hello-cargo.html

- ↑ rust modules https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/items/modules.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 rustup https://rustup.rs

- ↑ rust channels https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/channels.html

- ↑ rust pointers https://steveklabnik.com/writing/pointers-in-rust-a-guide

- ↑ rust smart pointers https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch15-00-smart-pointers.html

- ↑ rust references borrowing https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch04-02-references-and-borrowing.html

- ↑ rust raw pointer https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.pointer.html

- ↑ rust borrowed pointer https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/borrow/trait.Borrow.html

- ↑ rust reborrow https://github.com/rust-lang/reference/issues/788

- ↑ rust lifetime https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/scope/lifetime.html

- ↑ rust traits https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch10-02-traits.html

- ↑ Rust allocators https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/alloc/trait.Allocator.htm

- ↑ rust closures https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch13-01-closures.html

- ↑ rust mutable https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch03-01-variables-and-mutability.html

- ↑ rust mutable https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/scope/borrow/mut.html

- ↑ rust feerless concurrency https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch16-00-concurrency.html

- ↑ rust closures https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch13-01-closures.html

- ↑ rust destructors https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/reference/destructors.html

- ↑ rust Drop trait https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/trait/drop.html

- ↑ Rust operators https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/appendix-02-operators.html

- ↑ Rust operator overloading https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/trait/ops.html

- ↑ rust async programming https://rust-lang.github.io/async-book/

- ↑ rust Future https://rust-lang.github.io/async-book/02_execution/02_future.html

- ↑ rust Spawning https://rust-lang.github.io/async-book/06_multiple_futures/04_spawning.html

- ↑ rust Async runtime https://rust-lang.github.io/async-book/08_ecosystem/00_chapter.html

- ↑ rust streams https://rust-lang.github.io/async-book/05_streams/01_chapter.html

- ↑ axum https://github.com/tokio-rs/axum

- ↑ rust primitives https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/primitives.html

- ↑ rust cross-compilation https://rust-lang.github.io/rustup/cross-compilation.html

- ↑ rust lifetimes https://web.mit.edu/rust-lang_v1.25/arch/amd64_ubuntu1404/share/doc/rust/html/book/first-edition/lifetimes.html

- ↑ rust Arc https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/sync/struct.Arc.html

- ↑ rust move semantics https://stackoverflow.com/questions/29490670/how-does-rust-provide-move-semantics

- ↑ rust book https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/reference/introduction.html

- ↑ cargo book https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/

- ↑ rust language book https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/book/index.html

- ↑ rustc https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rustc/index.html

- ↑ std cargo https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/std/index.html

- ↑ rust code examples https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/rust-by-example/

- ↑ mandlebrot benchmarksgame https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_programming_languages

- ↑ mandlebrot benchmarksgames https://benchmarksgame-team.pages.debian.net/benchmarksgame/performance/mandelbrot.html

- ↑ https://web-frameworks-benchmark.netlify.app/compare?f=express,gearbox,vapor-framework,happyx,actix,activej,fomo,drogon,salvo,uwebsockets

- ↑ rust installers https://forge.rust-lang.org/infra/other-installation-methods.html

- ↑ rust cargo https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/guide/index.html

- ↑ Install Visual Studio on Debian12 https://linuxgenie.net/how-to-install-visual-studio-code-on-debian-12/

- ↑ VisualStudio download area https://code.visualstudio.com/download

- ↑ VisualStudio getting started https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/?dv=linux64_deb

- ↑ rust style https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.0.0/style/style/naming/README.html

- ↑ rust style advisory https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/style-guide/advice.html

- ↑ rust style guide https://doc.rust-lang.org/nightly/style-guide/

- ↑ rust comments https://doc.rust-lang.org/1.0.0/style/style/comments.html

- ↑ git markdown https://docs.github.com/en/get-started/writing-on-github

- ↑ markdown https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown

- ↑ rust attributes https://medium.com/@luishrsoares/exploring-rust-attributes-in-depth-ac172993d568#:~:text=Attributes%20in%20Rust%20start%20with,function%20and%20module%2Dlevel%20attributes

- ↑ https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch19-06-macros.html

- ↑ rust formatted print https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/hello/print.html

- ↑ rust formatting https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/fmt/

- ↑ rust type https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch03-02-data-types.html

- ↑ rust type conversion https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/conversion.html

- ↑ rust arrays https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.array.html

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 rust ,ove https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/keyword.move.html

- ↑ rust pointer https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.pointer.html

- ↑ rust reference https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.reference.html

- ↑ rust custom types https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types.html

- ↑ rust structure https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types/structs.html

- ↑ rust enum https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types/enum.html

- ↑ rust union https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/types/union.html

- ↑ rust constants https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/custom_types/constants.html

- ↑ rust literal https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/expressions/literal-expr.html#:~:text=Floating%2Dpoint%20literal%20expressions&text=no%20radix%20indicator-,If%20the%20token%20has%20a%20suffix%2C%20the%20suffix%20must%20be,the%20expression%20has%20that%20type.

- ↑ rust TypeName trait https://docs.rs/typename/latest/typename/trait.TypeName.html

- ↑ rust variables https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/variable_bindings.html

- ↑ rust variables https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/variables.html

- ↑ rust variable deferred initialization https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/variable_bindings/declare.html

- ↑ rust variable scope https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/variable_bindings/scope.html

- ↑ freezing https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/variable_bindings/freeze.html

- ↑ rust cast https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/types/cast.html

- ↑ rust literal type suffix https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/types/literals.html

- ↑ rust type inference https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/types/inference.html

- ↑ rust type alias https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/types/alias.html

- ↑ rust type conversion https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/conversion.html

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 from into https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/conversion/from_into.html

- ↑ rust string conversion and parsing https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/conversion/string.html

- ↑ rust statistics https://rust-lang-nursery.github.io/rust-cookbook/science/mathematics/statistics.html

- ↑ rust nalgebra https://docs.rs/nalgebra/latest/nalgebra

- ↑ rust Matrix https://docs.rs/matrix/latest/matrix/index.html

- ↑ rust complex https://docs.rs/num-complex/latest/num_complex/

- ↑ rust operators https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/appendix-02-operators.html

- ↑ rust operators https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/ops/index.html

- ↑ rust operator overloading https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/programming-rust/9781491927274/ch12.html

- ↑ rust trait https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.reference.html#trait-implementations-1

- ↑ rust if/else https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/if_else.html

- ↑ rust loop https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/loop.html

- ↑ rust while https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/while.html

- ↑ rust for range https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/for.html

- ↑ rust match https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/match.html

- ↑ rust match binding https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/match/binding.html

- ↑ rust if let https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/if_let.html

- ↑ rust let/else https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/let_else.html

- ↑ rust while let https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/while_let.html

- ↑ rust range expression https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/expressions/range-expr.html

- ↑ rust functions https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn.html

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 rust associated functions and methods https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn/methods.html

- ↑ rust closure https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn/closures.html

- ↑ rust iterator https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn/closures/closure_examples/iter_any.html

- ↑ HOF https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn/hof.html

- ↑ diverging https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/fn/diverging.html

- ↑ rust closure expression https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/expressions/closure-expr.html

- ↑ rust namespaces https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/names/namespaces.html

- ↑ rust path https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/paths.html

- ↑ rust prelude https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/names/preludes.html

- ↑ rust visibility https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/visibility-and-privacy.html

- ↑ rust std crate https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/std/

- ↑ std macros https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/std/#macros

- ↑ rust print! https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/std/macro.print.html

- ↑ rust println! https://doc.rust-lang.org/stable/std/macro.println.html

- ↑ box https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/box.html

- ↑ rust vectors https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/vec.html

- ↑ rust string https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/str.html

- ↑ rust option https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/option.html

- ↑ rust result https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/result.html

- ↑ rust panic https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/panic.html

- ↑ rust hashmap https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/hash.html

- ↑ rust HashSet https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/hash/hashset.html

- ↑ rust Rc https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/rc.html

- ↑ rust Arc https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std/arc.html

- ↑ rust threads https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/threads.html

- ↑ channels https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/channels.html

- ↑ rust Path https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/path.html

- ↑ rust File https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/file.html

- ↑ rust ChildProcess https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/process.html

- ↑ rust Pipe https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/process/pipe.html

- ↑ rust file system operations https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/std_misc/fs.html

- ↑ rust ownership https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch04-00-understanding-ownership.html

- ↑ rust asm https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/inline-assembly.html

- ↑ rust error handling https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch02-00-guessing-game-tutorial.html#handling-potential-failure-with-result

- ↑ rust ? error handling https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch09-02-recoverable-errors-with-result.html

- ↑ rust unsafety https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/unsafety.html

- ↑ rust linkage https://doc.rust-lang.org/reference/linkage.html

- ↑ rust debuging

- ↑ gdb cheat sheet https://darkdust.net/files/GDB%20Cheat%20Sheet.pdf

- ↑ rust druid https://linebender.org/druid/01_overview.html

- ↑ @zubiarfan https://practice.rs/

- ↑ rsut ? operator https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f82wn-1DPas